This year, I have been pondering the relationship between garden design and garden process. My reflections were particularly triggered by reading Larry Weaner and Thomas Christopher’s book, Garden Revolution, which argues in favor of a focus on “garden as process” rather than “garden as product.” (See Favorite Garden Books: Garden Revolution.)

This year, I have been pondering the relationship between garden design and garden process. My reflections were particularly triggered by reading Larry Weaner and Thomas Christopher’s book, Garden Revolution, which argues in favor of a focus on “garden as process” rather than “garden as product.” (See Favorite Garden Books: Garden Revolution.)

My thinking about this tension in garden design took a leap forward this summer when I had the opportunity to take two courses at the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens with Bill Cullina, President and CEO of the gardens. Bill was recruited to the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens from the New England Wildflower Society, where he was in charge of plant propagation. He is a knowledgeable horticulturalist, a scientist who gathers information through experimentation and observation, and a creative thinker.

The two courses I took with him were “Selecting Native Herbaceous Plants for the Maine Garden” and “Horticultural Ecology,” both required courses for the Certificate in Native Plants and Ecological Horticulture that I am working toward. Like all courses at the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens, these were intensive (each two full days) and they combined periods in the classroom with periods walking around the gardens to examine plants in situ. Walking around the gardens with Bill is an extraordinary experience, not only because he knows so much about plants and horticultural science, but because he seems to be intimately acquainted with every plant growing there.

Our first foray into the garden on the first day of the Horticultural Ecology class was to the rain garden immediately behind the Borsage Family Education Center, where classes are held. The Education Center is a LEED-certified building, and the rain garden for handling runoff from the roof was part of the design for LEED certification. As Bill pointed out and discussed the various plants growing in the rain garden, it became apparent that many (most?) of them had not been part of the original rain garden design. It seems that the design philosophy practiced at the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens is to begin with a planting designed to fit the site; then see which plants thrive, which do not and (most importantly) which plants not originally part of the design show up on their own; then edit.

Editing involves removing plants that do not thrive or are otherwise unsuitable for the place where they have been planted. One of the plants that volunteered to grow in the rain garden was common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), a plant which tends to form large clonal colonies. The milkweed was allowed to stay in one part of the rain garden, where it is completely surrounded by rock and has created a lovely island of milkweed. In the rest of the rain garden, where they were likely to become thugs, common milkweed seedlings were pulled up.

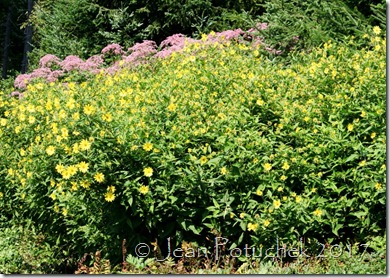

Another plant that had shown up as a volunteer in the rain garden and had been welcomed there was spotted Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium maculatum). Indeed, Joe-Pye weed has seeded itself in many parts of the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens; and its stately pink blooms are a glorious presence in the September gardens. In one part of the Haney Hillside Garden, Joe-Pye weed has created a beautiful combination by planting itself side-by-side with the perennial sunflower (Helianthus) ‘Lemon Queen’

Another plant that had shown up as a volunteer in the rain garden and had been welcomed there was spotted Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium maculatum). Indeed, Joe-Pye weed has seeded itself in many parts of the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens; and its stately pink blooms are a glorious presence in the September gardens. In one part of the Haney Hillside Garden, Joe-Pye weed has created a beautiful combination by planting itself side-by-side with the perennial sunflower (Helianthus) ‘Lemon Queen’

If one advantage of the botanical garden’s design philosophy is the creation of beautiful combinations like this one that weren’t envisioned in the original planting design, another advantage is the cost savings when plants are allowed to propagate on their own. I saw an example of this when I visited the garden in May and was struck by colorful masses of marsh marigolds (Caltha palustris) blooming around ponds in both the Lerner Garden of the Five Senses and the Children’s Garden. It turned out that only a few of these, along one edge of one pond, were part of the original planting; the rest had seeded themselves.

As someone who came to gardening from a love of wildflowers, I find this design/process/edit strategy very appealing. The concept of garden designer as editor provides a middle path between Thomas Rainer and Claudia West’s idea of creating designed plant communities (see Favorite Garden Books: Planting in a Post-Wild World), which can be intimidatingly complex, and Weaner and Christopher’s idea of creating gardens that mimic wild plantings by using communities of plants already found growing together in similar conditions. I like the idea of letting natural communities develop as volunteer wildflowers seed themselves into my designed gardens and of being more intentional about which self-sown volunteers stay and which ones get edited out.

As someone who came to gardening from a love of wildflowers, I find this design/process/edit strategy very appealing. The concept of garden designer as editor provides a middle path between Thomas Rainer and Claudia West’s idea of creating designed plant communities (see Favorite Garden Books: Planting in a Post-Wild World), which can be intimidatingly complex, and Weaner and Christopher’s idea of creating gardens that mimic wild plantings by using communities of plants already found growing together in similar conditions. I like the idea of letting natural communities develop as volunteer wildflowers seed themselves into my designed gardens and of being more intentional about which self-sown volunteers stay and which ones get edited out.

Filed under: Garden Books, garden design, garden education, wildflowers Tagged: Caltha, Claudia West, Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens, Eurtochium, Garden Books, Gardens to Visit, Helianthus 'Lemon Queen', Joe Pye weed, Larry Weaner, marsh marigolds, sunflower, Thomas Christopher, Thomas Rainer, William Cullina

![]()

Garden Revolution: How Our Landscapes Can Be a Source of Environmental Change by Larry Weaner and Thomas Christopher (Timber Press, 2016) is part of a trend in garden design to use natural plant communities as a model for gardening. In this sense, it fits together well with Darke and Tallamy’s 2014 book The Living Landscape (see my review

Garden Revolution: How Our Landscapes Can Be a Source of Environmental Change by Larry Weaner and Thomas Christopher (Timber Press, 2016) is part of a trend in garden design to use natural plant communities as a model for gardening. In this sense, it fits together well with Darke and Tallamy’s 2014 book The Living Landscape (see my review